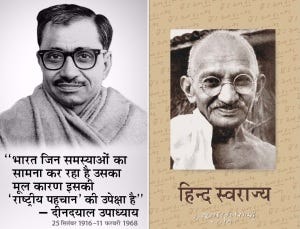

The Twelvetide of Martyrdom :: Mohandas Gandhi to Deendayal Upadhyaya

30th January (1948) - 11th of February (1968)

Mahatma Gandhi and Deendayal Upadhyaya shared the views that democracy in real sense can be attained only through proper and active participation of people.

They stressed on the collaboration of different political parties for attaining that.

Both believed in adoption of Swadeshi and decentralisation of social, economic and political powers.

In the 75th Year of Independence, a grateful nation would be commemorating the martyrdom of two of its leading ideological savants anchored into the Civilizational Foundations of Sanatan Bharat, though represented by two political camps spread over 12 days, starting from 30th of January to 11th of February.

Mohandas Gandhi who emerged as the major figure in India’s freedom movement stewarding the Indian National Congress in the 1920s encapsulating his political ideology in #HindSwaraj was tragically assassinated on 30th of January 1948 while Deendayal Upadhyaya, who curated the political ideology of #IntegralHumanism & an organizational base in Bharatiya Jan Sangh which has now evolved to Bharatiya Janata Party was found dead on the railway tracks of MughalSarai Junction (now Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Junction) on 11th of February 1968.

It would thereby be imperative to compare these two Political Giants of Modern India in this twelvetide of National Commemoration of their Martyrdoms drawn from American Scholar Dr. Walter K. Anderson’s work “Brotherhood in Saffron” & Dr. Abha Chauhan Khimta of HP University.

Whether comparisons are ‘odorous’ or not, only Dogberry, a character from “Much Ado About Nothing” and his creator Shakespeare were likely to know. But the common experience is that comparisons at times certainly odious. Bracketing Deendayal’s name with that of Gandhi is likely to strike some persons as sacrilegious.

Deendayal was so humble and unassuming that he himself would have brushed aside any direct or indirect hint that he was anywhere near Gandhi in political or spiritual stature.

How far were their ideologies similar and dissimilar to each other?

Good Governance

Like Mahatma Gandhi, Deendayal Upadhyaya also talked about Good Governance. According to Upadhyaya the problems of Bharat were not merely political, social, economic or cultural but of establishing in our society those values of life which can solve these problems.

The root cause of all this is political corruption. Therefore, unless we bring about a qualitative change in politics, we shall not be able to have a good government run by good people. Deendayal was the ideal of such a leadership.

‘The king is the master of the state which he does not enjoy for himself- this is the principle which is true for all times. According to him, we need leaders who do not serve their self- interest and who, rather, serve others with a sense of thankfulness.”

Mahatma Gandhi had also referred about good governance. According to him, political swaraj in the sense of transfer of power from one set of rulers to another set did not satisfy him.

He said, “I am not interested in freeing India merely from the English yoke. I am bent upon freeing India from any yoke whatsoever. I have no desire to exchange ‘king log for king stork’. Hence for me the movement of swaraj is a movement of self-purification”.

Even when one’s own brothers were ruling oneself, one might not have swaraj and might have swaraj under foreign rule. Gandhi was opposed to all types of oppressions.

Democracy

Today, democracy has been reduced to a race for power among the powergroups and our politics is principled only in name and in reality it is nothing but power-oriented opportunism.

Deendayal used to say,

“Only the common man should be made the GOD of Democracy”.

“Only the common man should be made the GOD of Democracy”.

Speaking on the relations between political parties and the people, Deendayal had stated,

“If you are democrats, you should follow the dictates of your own discretion rather than accept any other authority. Political parties are constituted to function as representatives of the people. Their only base is the power of the people. It is the people who confer on them the capability to function; it is the people who create them and, through them, shape their own future. Therefore, a political party is not merely a conglomeration of power-hungry people. It is rather, a unified entity and a disciplined organization of god oriented and committed people working for a specific ideology.”

Thus Deendayal emphasised on the role of people in Democracy. According to him, political parties should work as unified entity for the welfare of the people. Deendayal laid down the principle that national interest is always for above party interest. We stressed that just as an individual is not supposed to sacrifice the national interest for the sake of his personal interest, so is a party supposed not to serve its own interest to the detriment of national interest. Thus the focal point of politics was the nation.

Similarly Mahatma Gandhi’s true democracy was participatory democracy. It was the idea of participation by the whole community in the political process. It based political authority on the will of individuals who by aprocess of cooperation make decisions that were binding on all. Gandhi considered that citizens had a duty to decide to whom they should give their loyalty and support and under what conditions. Their self-respect and dignity required that their loyalty should not be unconditional or taken for granted. When a law was just, they had a ‘sacred duty’ to give it their ‘willing and spontaneous obedience’, if it was unjust or morally unacceptable, they had the opposite duty. To obey it was to ‘participate in evil’ and incur moral responsibility for its consequences.

Swadeshi & Decentralisation

While we all know about Gandhian advocacy in Hind Swaraj, Deendayal’s thinking encompasses fourfold objective of nationalism, democracy, social strength and swadeshi.

He once said, “The economy policy suitable for the present situation can be described in two words, Swadeshi & Decentralisation. Today, Swadeshi seems to have become an out of date and retrograde concept. We accept foreign aid with a great sense of pride. We are making use of foreign help in our conceptions in the field of management, in procuring capital investment and in the field of production. Even our ideal of consumption of consumer goods is based on the foreign pattern. This can never be the path of progress and development for us. It is a slavish tendency which ignores our own entity and to which we are becoming slaves. To be honest, the constructive aspect of the concept of Swadeshi should do from the basis of our economic policy.”

He stressed that socialism was becoming another name of all devouring statism. Poverty eradication programmes achieved nothing except carrying the burden of the administration. In such a situation, the freedom, the honour of the individual and democracy could be protected only through Panchayati Raj and Decentralised Economy.

Spiritual Development

Like Mahatma Gandhi, Deendayal Upadhyaya believed that it is true that the body must be attended to properly but it is necessary to remember that the purpose of a healthy and strong body was as the chief instrument in observing the dictum of Dharma.

He mentioned about Dadhichi Saint who immolated himself so that a powerful weapon may be made from his bones for slaying a powerful demons. Thus Upadhyaya’s philosophy of integral humanism envisages the enjoyment of the various categories of happiness but at the same time emphasises restraint and sacrifice and considers that with the investiture of authority is inseparably bound the performance of duty. The individual happiness must not only never stand in the way of social progress but must be congenial and complementary to it.

The central idea of the philosophy of Integral Humanism was that the family is the first training ground for an individual towards social life. Mutual affection, willingness to work and suffer for others, tolerance and all such virtues necessary for social welfare are easily imbibed in family life. To extend the family concept first to the society and then to the universe is the direction of spiritual development.

While mentioning about the supremacy of the individual or society, Upadhyaya says, “Any healthy thinking takes into account the interests of both the individual and the society.”

People ask us whether we are individualists or socialists. Our answer would be, “We are both”. According to our culture we can neither ignore the individual nor lose right of society’s interests. We do take into account the social interests and so we are individualists. We do not consider individual supreme and so we are not individualists. But we do not also think that society should have power to deprive an individual of all his freedom and thus exploit him like a lifeless thing, so we are not socialists either. One cannot conceive of a society without individuals and the individuals have no value without society. Bharatiya culture has set both in proper perspective and jointly considers the welfare of both.

According to philosophy of integral humanism, a society is a living organism. And since every living organism has a body, a mind, intelligence and a soul, a society also has these four constituents. Upadhyaya says that economic planning is important. He says that this planning must provide suitable work for every physically fit person and the job must be such as to give a reasonably adequate income. Only through such planning a country’s wealth can increase.

Both Upadhyaya and Mahatma Gandhi insisted, not on mass production but on production by the masses.

National wealth must accrue out of the Artha Purushartha of the masses i.e. out of the initiative and the urge to work of the masses. Wealth created by the efforts of a few or by the use of modem machinery is not for the good of the society. Similarly, the achievement of the Artha Purushartha for the society must be brought about according to regulation and spirit of Dharma.

State

In the Artha-Purushartha of the society, along with economic policy one has also to consider the power of the state to defend the good and punish the guilty. If the state is too weak to do this or if it makes indiscrete use of its power then instead of it being a Dharma-controlled state it becomes a Police-Raj and ruins the society.

Upadhyaya stressed that state is meant for the protection of the nation. Chiti is the Sanskrit word for society’s soul equivalent to individual soul. And RashtraDharma or Nation-Dharma consists of the rules for the expression and practice of this chiti (A people’s ethos). The duty of the state is to observe this Rashtra-Dharma and in order to enable the state to do this duty certain power have been conferred on the state by the people. The state is expected to use these powers with discretion. But often the government becomes oblivious to its duties.

In the language of the four-fold Purusharthas, when Artha Purushartha is separated from Dharm Purushartha, it starts the moral degradation of the rulers.

While discussing Moksha Upadhaya said, “Liberation or Moksha is not an individual affair; it is social. Some people have a wrong notion that they can seek individual salvation even when the society is in disarray. It is only when society is liberated, uplifted and ennobled, that an individual can be at peace… He respected all Indian languages. But he could not bear the idea that English should be imposed on the country; it was foreign and not more than one percent of the masses understand it.”

Mahatma Gandhi followed the path of Satyagraha for the attainment of swaraj as well as it became the creed for whole life.

While Upadhyaya expressed his views by saying,

“The run of events during the last fifty years has been such that the moments we talk of agitation, there come to our mind, jail, satyagraha, nonpayment of taxes and revenue etc. Really speaking, no independent country should have any need of such agitations. But fact is that such a need is felt here. And this shows the government’s unwillingness to honour the people’s will.

We must, however, bear in mind that such an agitation is the last weapon we should resort to. Jana Sangh does not believe in ‘satyagraha’ as its creed. But only when it is forced by circumstances, does Jana Sangh resort to such means in order to bend the government to the popular will.

We desire that meetings, resolutions and memorandum should be adequate for the expression of the popular will and for government’s implementation thereof. In the absence of such peaceful expression and implementation, the whole atmosphere will be in a state of great strain.”

Deendayal chose Dayananda and Tilak as the models to copy. These giants would brush aside everything else if it came in the way of their faith in our culture and their aspirations of social and national renaissance. Tilak did not compromise on national interests.

Deendayal disclosed that it would be unwise to uproot our national century-old industries in the villages.

Though there are many weaknesses in these small industries. It would be essential to make them economically viable in the course of planning. Our village industries should be transformed into viable units of production in the economy. If we inclusively emphasise modernised technology, old would be discarded. This would ultimately result in the waste of capital blocked in old industries. We cannot afford to allow this wastage of capital, because we are short of capital accumulation for progress.

Deendayal further disclosed in his book on Indian Economic policy that,

“We may produce with, the help of Westernised heavy and complicated technology, goods on mass scale. But this process cannot sustain an eternal and revolutionary transformation in the economy.

It is necessary that while the pressure of population on agriculture is reduced, we should be able to promote the rural industries which are interconnected in the harmonious way with agriculture.

Instead of giving priority to large scale industries, we must give priority to small size enterprises.

Production units worked by a few workers, and with small machinery and small sized instruments, would be more useful ultimately in the correct situation.

We will have to consider the foundation of Gramodyog smaller size enterprises, and the workers therein need our attention in the process of planning.”

In this context Gandhian views of Sarvodaya and Gramodyog economy may be greatly relevant.

All sections of the people should receive benefit more or less in the process of the development. That economy is best which can achieve progress of all. Mahatma Gandhi connected this by Sarvodaya. Next to agriculture, Mahatma Gandhi was giving priority to village industries. He emphasised that poverty and unemployment cannot be removed by promoting the large scale industries and big industrial unit. It is necessary to promote decentralised village industries which are labour intensive.

Gandhi said,

“If you find a better alternative to charkha, you may bum Charkha; however, millions of villagers should not be removed from their homes and they should not be divorced from their small piece of land. This is possible only with the help of charkha which alone helps to get gainful employment, as it brings a minimum income from the same.”

The above mentioned views of Mahatma Gandhi could be compared with similar views on Deendayal, who however, was not opposed to use machineries and appropriate technologies in the village industries. If machine creates unemployment or increase unemployment then machine should be opposed. Oil engines, electric motors etc. had no place in the village industries of Mahatma Gandhi. Deendayal however did not oppose machinery in this domestic manner.

Following is a comparative analysis of the personalities of these two giants of Modern India

Gandhi and Upadhyaya were primarily organisers and only secondarily interested in philosophic speculation

Indeed neither were intellectuals in the conventional sense of the term – that is erudite and sophisticated men with academic qualifications and long lists of books to their credit. Neither wrote systematic treaties on morals and politics, nor was either a philosopher, in the sense that they were not particularly interested in abstract theoretical formulations. Gandhi, for example, told a scholar researching the concept of *Satyagraha*: “but satyagraha is not a subject of research – you must experience it, use it, live by it”. Similar anecdotes could be repeated of Upadhyaya.

Both Gandhi & Upadhyaya were charismatic figures

Though Gandhi had the larger impact, in part because so many considered him a saintly figure, if not a saint. His asceticism convinced many that he was able to realize ideals which many held, but which few could realize. Gandhi transformed the Indian National Congress from a rather staid debating forum of the anglicised upper class into a rationalised organization that encompassed a wide range of activities that touched on the lives of the masses. His organizational skills, combined with his charismatic appeal as a Mahatma, transformed the Congress into the effective action arm of the independence movement.

Upadhyaya also possessed the characteristic of the saintly. He gave up the calling of a profession and a family to dedicate himself to the Motherland. His life was Spartan and his adherence to moral standards was of an unusually high order. These traits brought him the respect, if not devotion, of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) Swayamsevaks in the United Provinces where he served as a Pracharak (full time worker) from 1942-51, the latter few years as assistant state organizer of the RSS in the now-renamed Uttar Pradesh. He has a similar effect on the cadre of the Jan Sangh where he was one of the two All-India Secretaries after the formation of the party in 1951 and from 1952-67 the All-India Secretary.

Dr. Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, president of the newly founded party for a few years before his untimely death, commented that were he to have several more men like Upadhyaya he could transform India.

Upadhyaya certainly transformed the Jan Sangh. He took over the management of the party at the death of Dr. Mukherjee in mid-1953 at a time when many questioned whether it could survive without a towering figure such as Mukherjee to lead it. There was strife in the small party over control of the executive and confusion over its program. He instilled discipline, broadened participation, recruited a dedicated cadre and shaped its program to espouse the interests of those with little money, power or status.

While there were a few minor defections during his life, the Jan Sangh was the one major India party which suffered no significant fissure. That is a testimony to the cohesive organization that he mulled.

Yet, it must be recognized that he was never a mahatma, nor is there any indication that he aspired to such a status.

Indeed, he even tried to AVOID public attention.

From both his writings and talking with people who knew him, we get the image of a man who felt uncomfortable in the limelight, who believed that the organization and its goals were incomparably more important than personal recognition.

So self-effacing was he that, for example, he often would not sign articles that he wrote for Panchajanya, a journal which he edited from Lucknow in the late 1940’s.

Consistent with the RSS tradition from which he came, he viewed personal publicity as a detriment to the cause – and the cause was organising Indians to overcome the internal divisions that, he felt, had historically exposed the country to outside subversion and that has undermined the willing ness to make the sacrifices necessary for economic and cultural revival.

Unlike Gandhi, Upadhyaya was not a religious man in conventional sense of the term

While he was stepped in the Hindu traditions, particularly Vedant, he was not a worldly sadhu and he was not moved to act by religious precepts.

However, like Gandhi, he rejected post-Machiavellian trend of western thought that posited the separation of religious and political ideals.

In their attempt to fuse the two concepts, Gandhi and Upadhyaya drew on the traditional Hindu concept of Karma Yoga, or spiritual realisation through social work.

Both accepted the traditional notion that Dharma (individual and social duty) is the legitimate guide for shaping Artha (interest) and Karma (pleasure).

Yet, their approach to the determination of dharma was quite different.

Gandhi stressed the individual’s quest of satya (truth) to inform him of the ethical rules that govern man’s behavior. This approach stands out in his oft-quoted assertion that “I would reject all authority if it is in conflict with sober reason or the dictates of the heart. Authority sustains and ennobles the weak when it supplants reason (that is) sanctioned by the small voice within”.

Gandhi’s focus on individual effort has led some to conclude that he was a moral anarchist, if not also a social anarchist. For example, he wrote in Young India (March 1931), “there is no freedom for India so long as one man, no matter how highly placed he may be, holds in the hollow of his hands the life, property and honor of millions of human beings. It is artificial, unnatural and uncivilised institution”.

Gandhi of course, was not an anarchist in either sense, for he also accepted the Vedantist notion that there is an underlying truth potentially open to all. Moreover, he had a respect for traditional institutions such as the Panchayata and the varna system, both of which specified special social duties and responsibilities.

Upadhyaya on the other hand,

emphasised the collective wisdom of the nation as the authoritative voice of Dharma.

emphasised the collective wisdom of the nation as the authoritative voice of Dharma.

However, he was also apprehensive that the majority might not always properly understand the laws of Dharma. “But even the people are not sovereign because people too have no right to act against Dharma”

Furthermore, “the truth cannot be decided by the majority; what the government will do will be decided by Dharma.”

He does not define who the legitimate interpreter of dharma is.

It is not unreasonable to conclude from his writings that he thought democracy the system most likely to approximate dharma since it provides an opportunity to detached men dedicated to national well-being to shape and correct public opinion.

The centrality of the nation in his thought rests on notion that it has a soul (i.e, “chiti”), shaped by experiences within a given geographical space and motivated by an over-arching ideal.

In describing the nation, he often drew on the metaphor of an organism, in particular the human body, in which each part has its true reality only in the particular function it fulfills within the whole.

“A system based on the recognition of this mutually complementary nature of the different ideals of mankind, their essential harmony, a system which devises laws which removes the disharmony and enhances their mutual usefulness and cooperation, alone can being peace and happiness to mankind; can ensure steady development”

Indeed, it is this organic concept of the nation that, it his view, has been the ideal that kept alive the Indian nation through the vicissitudes of time.

It is its unique contribution to political philosophy. His major philosophic argument against the ruling political elite of his time was his conviction that they advocated western notions of society and, in the process, undermined the integral unity that has sustained Bharatiya civilization.

He was far less committed to traditional institutions than Gandhi.

His writings are sprinkled with attacks on the caste system, as practiced.

In his view, all institutions are derivative and, when they cease to fulfill the integrating function, they should be revised or abandoned.

It is not surprising that orthodox Hindus were among the major critics of the Jan Sangh.

Gandhi’s political object was Swaraj (self-rule). But he interpreted Swaraj as more than mere independence from the British; it carried the meaning of an all-embracing self-sufficiency down to the village level.

Self-sufficiency translated into a concrete program of action that led him to espouse Swadeshi (self-reliance) and the central effort during the years of the nationalist struggle for Swaraj lay in the propagation of Khadi (hand-spun cloth).

Swadeshi served not only an economic function in actual supply of cloth; it also carried significant ideological implications. It was the central piece of his elaborate constructive work program. It was the symbolic representative of his effort against centralized industry and urbanization which he thought degraded the worker. (These products of modernization were attacked vigorously in his tract – Hind Swaraj, written in 1909). His condemnation of western materialism led him inevitably to support the concept of self-governing village communities and a simple low-technology system of production.

Upadhyaya’s writings demonstrate a comparable outrage against the effects of western models of development.

In a series of lectures in Poona in 1964 on Integral Humanism, later adopted as the official ideological statement of the Jan Sangh, he lashed out at both Socialism and Capitalism. “Democracy and Capitalism join hands to give a free reign to exploitation. Socialism replaced Capitalism and brought with it an end to democracy and individual freedom”.

In their place, he proposes a model that takes into consideration all aspects of the human condition, “body, mind, intelligence and soul – these four make up an individual”.

In practical terms,, the notion translated into a decentralised economy and political system in which citizens have a meaningful voice in the production process and in their own governance. This populist conception assumes a leveling in both economic and political power. Marked differences in access to power or economic resources would undermine the harmony he believed to be the essential cement of the good society.

Upadhayaya was not, however, adverse to the selective adoption of science, technology or even urbanization.

He thought that they should be adapted to local conditions to improve the economic well-being of the population. Societies must produce enough to feed, cloth, house, educate and employ those within it. To do less would result in misery and strife, thus disrupting the harmony necessary for well-being of the collective. At the same time, however, he felt that consumption should not degenerate into consumerism.

“From this point of view, it must be realized that the object of our economic system should be, not extravagant use of available resources, but a well regulated use.

The physical objects necessary for a purposeful happy and progressive life must be obtained. The Almighty has provided as much. It will not be wise, however, to engage into a blind rat-race of consumption and production as if man is created for the sole purpose of consumption.”

Both Gandhi and Deendayal were suspicious of political power and its corrupting effect on public figures.

Neither held a political office and neither aspired to do so.

Gandhi a few months after India attained independence told his closest colleagues,

“By adjuring power and by devoting ourselves to pure and selfless service of voters, we can guide and influence them. It would give us far more real power than we shall have by going into government…Today politics has become corrupt. Anybody who goes into it is contaminated. Let us keep out of it altogether. Our influence will grow thereby.”

His advise, of course, was rejected by most of his Congress colleagues.

Ironically, Upadhyaya, the leader of a political party, would probably have subscribed to his view of politics. He wrote, “Today politics ceased to be a means. It has become an end in itself. We have today people who are engaged in power with a view to achieving certain social and national objectives”

Nevertheless, he thought it important, if not crucial, for the detached man of good will to remain in the political arena to help shape public opinion in the path of “Truth” (or Dharma). Consequently, he placed great stress on recruiting to politics men of high moral rectitude.

Despite the many differences between the two men, both came to the conclusion that it is the quality of men in society who will ultimately determine the nature of the state. This is at variance with most contemporary western political though (both speculative and empirical) which argues that conflicting interests are the major forces that shape the state and its policies.

Whatever the merits of Gandhi’s and Upadhyaya’s views on the issue, their intense interests in the types of people who worked around them were of fundamental importance in their successful organization-building efforts.

Institutions of all denominations are invited to Nominate their Reengineering Initiatives latest by Republic Day 2023 at www.rethinkindia.org/g20 which shall be presented on Integral Humanism Day, 11th of February 2023.